Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, a Nobel Peace Prize winner and the first woman to be elected president of an African country, has long been heralded as a leading force in putting an end to civil wars and advancing the rights of women.

But, she's remained uncharacteristically silent on the issue of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) in Liberia.

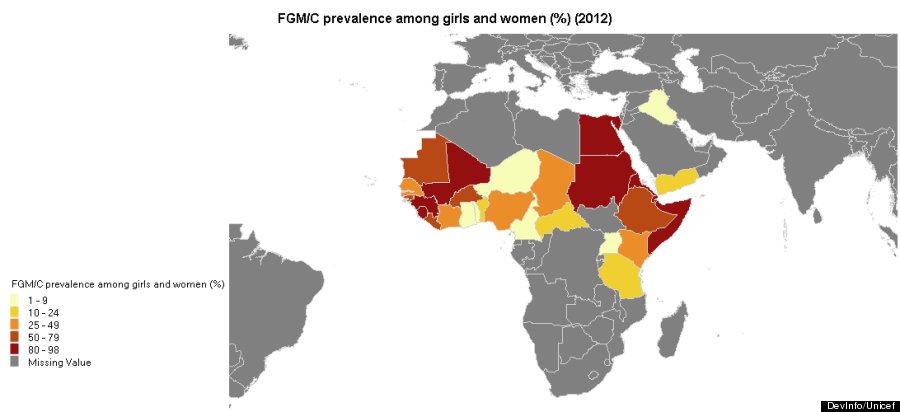

The human rights issue has resurfaced once again, as Thursday marks the U.N.’s International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation. According to the U.N., 125 million girls and women in areas of Africa and the Middle East -- where the practice is concentrated -- have undergone FGM/C. The procedure entails partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons, according to the World Health Organization.

While laudable gains have been made worldwide in reducing the number of FGM/C cases, Liberia remains one of the most difficult countries for advocates to permeate.

There, the procedure is carried out by a powerful secret society called the Sande, the Thompson Reuters Foundation reported. Girls who are cut by the Sande are told that if they reveal anything about the procedure, they or a member of their family will be killed.

"Liberia is very tricky," Grace Uwizeye, FGM program officer at Equality Now -- a group that works to protect the rights of women and girls -- told Reuters. "The secret society makes it very difficult to penetrate or even to start talking about FGM because people are just scared. You have to make sure people understand it’s OK to talk about FGM."

Girls, and sometimes even toddlers and babies, are taken to Sande "schools" to learn about marriage and motherhood, and getting cut is required for graduation, the Global Post reported in 2012. Priestesses pin down the girls and remove their clitorises with knives or razor -- without providing an anesthetic.

A mother holds her daughter's hand as she is circumcised in Indonesia.

The cultural practice was originally meant to ensure a girl’s status, marriageability, chastity, health, beauty and family honor, according to a UNICEF report released last summer.

However, experts now say that FGM/C is no longer tied to marriageability and is most strongly connected to concepts of personhood and religious identity.

But the numerous and complicated health risks remain the same.

Immediate complications include bleeding and infections, according to UNICEF. Long-term consequences include damage to adjacent organs, sterility, recurring urinary tract infections, birth complications, the formation of dermoid cysts and even death.

According to UNICEF, 66 percent of women and girls in Liberia undergo FGM/C. While it certainly doesn’t have the highest instance of FGM/C cases -- 98 percent of women of in Somalia have been cut, for example -- the U.N. still considers it to have a "moderately high prevalence of cases."

Former circumciser Mariam Coulibaly displays the tools of her trade, a knife handed down to her by her mother and herbs to heal the wounds, at her home in Salemata, southeastern Senegal.

Additionally, girls and women from the poorest households are twice as likely to have experienced FGM/C as those from the richest households, the report found.

While leaders around the world have been increasingly speaking out against the practice, Liberia has remained decidedly quiet.

The United Nations General Assembly banned FGM in 2012, and as of July, 24 African countries have passed laws banning the procedure,

Liberia has not been able to follow suit. In 2011, the Internal Affairs Minister Nelson Blamo vowed to draft a law banning FGM/C and President Sirleaf even attended a ceremony to mark the event, according to New Narratives.

However, the government never followed through on enacting the law.

While Sirleaf is expected to make a proclamation on Thursday to mark International Day of Zero Tolerance of FGM, advocates feel that they have had to shoulder too much of the burden of putting an end to the practice.

"This issue has been left for civil society to deal with for far too long," Efua Dorkenoo, advocacy director for Equality Now’s FGM program, told New Narratives.

Activists who have risked speaking out have suffered greatly.

In 2012, Phyllis Kimba's house was burned down the day after she spoke at the U.N. about female genital mutilation in Liberia, according to the Global Post.

When well-known Liberian journalist Mae Azango wrote a story exposing the risks of FGM/C for Front Page Africa in 2012, she was immediately met with death threats and forced into hiding.

Mae Azango, a journalist for FrontPage Africa, received death threats after publishing a piece in 2012 about the health risks of FGM/C

Azango's adversaries told her that would "grab [her] and put [her] in the Sande bush and cut [her]," according to the Daily Beast.

She has remained committed to speaking out about the cause, though.

Encouraging journalists, like Azango, to expose the groups that still practice FGM/C and making such writings more available to women and girls could be key in tackling the issue in Liberia, experts say.

In its exhaustive report last year, UNICEF found a lower instance of FGM/C among educated girls who had been exposed to such media messages and discourse that denounce the practice.

The human-rights organization has also suggested working with local cultural traditions rather than against them, and finding ways to reveal the hidden attitudes that actually oppose the practice.

"As with all deeply-entrenched practices, achieving the end of FGM will take action at every societal level. Condemnation and laws and policies banning the practice are important, but will not be enough," John Ashe, president of the U.N. General Assembly, said in a statement on Thursday. "The need for governments, religious leaders, health workers, countries hosting practicing migrant communities, and grass roots organizations to join forces to end FGM in one generation is now more urgent than ever."