A deadly attack by an avowed white supremacist shocked the nation. The president’s response came swiftly, and triggered raw emotion. Despite a sometimes strained relationship with the White House, corporate board rooms stayed silent, spared the need to weigh in.

That was 2015.

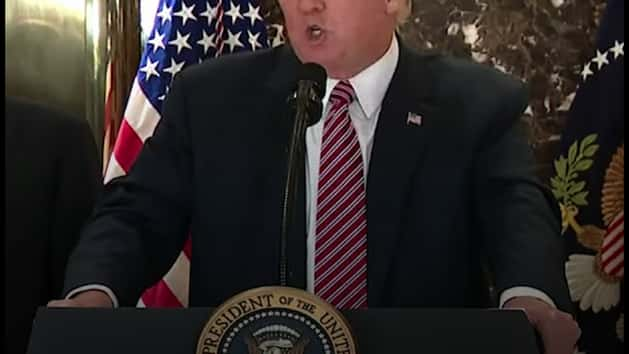

This week, chief executives at some of the country’s biggest companies tossed out usual protocols and disavowed the sitting commander-in-chief after President Donald Trump refused to single out the white supremacists and neo-Nazis who rallied in Charlottesville, Virginia, last weekend.

Two days of protests ― featuring torch-wielding, swastika-toting, Nazi-saluting protesters opposed to removing a Confederate monument ― turned deadly when a marcher drove a car into a crowd of counter-protesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer. Despite calling racism “evil” at a press conference two days later, Trump said the march drew some “very fine people,” a message white supremacists interpreted as nearly-explicit approval.

Big companies are by their nature risk averse when it comes to wading into political controversy. To prevent alienating customers and partners, they traditionally maintain political neutrality on issues that don’t directly intersect with their business interests, and cultivate friendly relationships with sitting administrations. But the reputational peril posed by staying silent on an issue as morally one-sided in mainstream politics as defending white supremacists proved too great this week.

“It’s not worth the risk to business,” said Jonathan Bernstein, founder of the consultancy Bernstein Crisis Management. “They’re realizing very quickly that they don’t want to be associated in any way with the Trump administration and the Trump White House.”

The exodus of corporate chieftains from Trump’s side began Monday, when Merck CEO Kenneth Frazier ― the only African-American on the president’s American Manufacturing Council ― quit “as a matter of personal conscience” and “to take a stand against intolerance and extremism.” Hours later, Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank and Intel CEO Brian Krzanich followed suit, even after Trump called out the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis in a damage-control speech.

Trump denounced the executives as “grandstanders” and vowed to replace them, but that did nothing to stop more executives from fleeing. Public pressure began to mount as nearly half the council stepped down in protest. That left consumer-facing brands particularly at risk. No members of the president’s other business advisory panel, the Strategic and Policy Forum, had yet dropped out, but Walmart CEO Doug McMillon excoriated Trump’s response to the Charlottesville tragedy in a rare public rebuke.

On Wednesday, in the face of possible boycotts, furious calls and social media messages, the remaining corporate executives agreed to disband both councils, though Trump took credit for dissolving the groups on Twitter.

By the end of the week, more than half of the Commerce Department’s Digital Economy Board of Advisors had also resigned, according to a report in Politico. That group included Mitchell Baker, executive chairwoman of Mozilla.

The week’s events illustrate the evolving nature of corporate power in U.S. politics. The Supreme Court’s 2010 decision known as Citizens United gave wealthy donors, including big corporations, nearly unlimited spending power in elections, in many cases reducing the influence ordinary constituents have over their elected officials. Coupled with partisan gerrymandering, which has allowed leaders to carve out districts that make political opposition almost impossible, lawmakers in Congress are increasingly unaccountable to the voters they ostensibly represent.

The backlash to Trump’s Charlottesville response put that on full display. By Tuesday, Republican lawmakers began offering pointed, if mealy-mouthed, condemnations of the president’s stance. But where senators and representatives offered words, corporations ― facing similar public pressure ― took action.

Of course, distance from the leader of the ruling political party won’t cost executives their jobs like it might lawmakers facing reelection in an era of hyper partisanship. At a particularly circus-like time in politics, this gives companies the ability to “become the adults in the room,” said Davia Temin, a management coach and reputation consultant who worked with some of the companies whose leaders resigned from Trump’s councils this week.

“Business has a planning and strategic horizon that is further out than four years or eight years or 12 years,” she told HuffPost. “They can actually have a counterpoint and be the counterbalance to the short governance by tweet.”

Trump has posed a challenge to businesses since he kicked off his presidential campaign by disparaging Mexicans as rapists and drug dealers and vowing to ban Muslims from the country. Last year, corporate giants such as Apple, Microsoft and Coca-Cola withheld funding from the 2016 Republican National Convention once it became clear Trump would clinch the nomination. Hewlett Packard Enterprise CEO Meg Whitman, a major GOP donor, reportedly compared Trump to Hitler and Mussolini during a private political summit. And BuzzFeed turned down ad money from the Republican ticket.

The pressure has hardly eased up since Trump took office. Before it’s dissolution this week, the Strategic and Policy Forum saw three of its members step down earlier this year to protest separate Trump decisions they deemed indefensible.

“Business ... can actually have a counter point and be the counterbalance to the short governance by tweet.”

- Davia Temin, a management coach and reputation consultant

In February, Uber’s then-CEO Travis Kalanick stepped down in hopes of distancing his ride-hailing service from Trump’s executive order barring travelers from several Muslim-majority nations. In May, Tesla and SpaceX chief Elon Musk resigned after Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris climate accord left him “no choice.” Walt Disney Company CEO Bob Iger also resigned over the president’s decision to pull the U.S. out of the historic climate agreement, which was signed by every country except Syria and Nicaragua. Notably, even oil majors that funded campaigns to undermine climate science urged Trump to stay in the pact.

Numerous tech companies denied services to the white supremacist web site The Daily Stormer last week, effectively taking it offline. “I woke up this morning in a bad mood and decided to kick them off the Internet,” Cloudflare CEO Matthew Prince wrote in an email to staffers. Free speech advocates argue that private companies should not decide what content deserves to be on the internet.

When Texas lawmakers tried to pass a transgender “bathroom” bill this year, businesses fearing statewide boycotts lined up against it, playing a key role in its (at least temporary) defeat. A host of major corporations opposed similar legislation in North Carolina, which was signed into law in 2016.

Corporations have become much more sensitive to long-term reputational damage, Temin said. As an example, she pointed to BP in 2010. The oil giant’s chief executive ignited a firestorm when he said, “I’d like to have my life back,” as millions of gallons of crude gushed into the Gulf of Mexico during the Deepwater Horizon disaster. The comment, she said, cost the British executive his job.

“If you become a pariah like BP did through so much insensitivity in the middle of a crisis ― their CEO was out,” Temin said. “He probably did a lot of the right things, but didn’t say the right things.”

To be sure, business leaders standing up to Trump’s coddling of white supremacists hardly means they are cutting off communication with the White House. Despite protests during the campaign, business leaders sidled up to Trump after his surprise victory in November, particularly once he made deregulation and tax reform the bedrock of his policy agenda. The same companies who distanced themselves from Trump this week are likely to keep lobbying the White House in the months and years ahead.

“Businesses will continue to engage on the issues important to the American economy, just through different venues,” Michael Steel, managing director at Hamilton Place Strategies, a public affairs firm that represents a number of financial services clients, told Politico. “Many people in the business community are frustrated by the president’s words and tweets on Charlottesville, but that does not change the importance of policies that make life better for the economy and the American people.”

Sign up for the HuffPost Must Reads newsletter. Each Sunday, we will bring you the best original reporting, long form writing and breaking news from The Huffington Post and around the web, plus behind-the-scenes looks at how it’s all made. Click here to sign up!