One of the enduring foundation myths of modern Australia has been that of the macho pioneer, bottling emotions and overcoming the odds through hot work and cold beer. Nowhere was this myth perpetuated more than rugby league, a hard working class game designed to test courage with a strict code of conformity. Aboriginals, Polynesians, Melanesians and Southern European migrants provided the game’s first diversity from its Anglo-Celtic base and these interlopers were accepted if they complied with the code and “copped it sweet”.

The code had no place for homosexual men and to be labeled gay was a slur implying weakness. And that’s the way it remained until a pioneer smashed the stereotype, becoming the game’s first openly homosexual player, a precursor, a full 20 years before Keegan Hirst, the Batley Bulldogs player who this weekend became the first British player to do likewise.

“Until Ian Roberts came out we thought all gay guys were weak,” says Mario Fenech, the former South Sydney Rabbitohs captain and Roberts’s team-mate. “I had no idea but he sharpened me up.” Fenech remembers Roberts as one of the toughest he had played with or against and the first of the new athlete prototype that heralded the “changing of the guard”. Fenech warmly recalls a kind off-field personality: “With everything he’s been through, what a great man, fun to be around and caring.”

Ian Roberts was born in Chelsea, London, in 1965 to English parents who migrated to Australia two years later as “10-pound Poms” on a government assisted scheme guaranteeing accommodation and a job. “I was brought up in an English household and Australia existed outside the front door,” he says while enjoying an afternoon coffee at a cafe in Redfern, the heart of south Sydney. “Family was everything, my dad was an ex boxer and a hard construction man and my mother was conservative and hard working.”

Roberts has just turned 50. He is fresh off the morning shift for Virgin Airlines at Sydney Airport and his phone is running hot. Back in Australia after a 10-year stint in Hollywood, he is enjoying some stability. “Acting is a very inconsistent industry and it’s nice for me to work in a normal environment,” he says. Some of his new workmates, particularly old rugby league fans, get excited when they first meet him but after a few weeks he simply becomes Robbo. “We’re all equals,” he says, “my past means nothing.”

Like most working-class youngsters in south Sydney he loved rugby league, but there was a complication – off the field he was only interested in boys. His first crush was Les McKeown of the Bay City Rollers and he had his first affair at 12, kickstarting a life of denial and fear.

At Maroubra Bay high school he withdrew into his shell when the call of “poofta” darkened the playground with the aim of ridiculing a small group of “queers”. Roberts felt he should have spoken out. They were his tribe and shared his feeling of isolation. “I used to feel bad inside not standing up for them. They were brave and I felt like a fraud.”

On the rugby league field Roberts was a rising star of the South Sydney juniors, but off field he didn’t belong. His father Ray was his best friend and was openly spiteful about anything gay he saw on television. “His comments made my skin creep and seared fear into my brain,” Roberts says. But he was safe, as long as he didn’t “let the family down”. His dad told him he needed a trade, so he left school early and became a qualified electrician.

At the age of 17 rugby league had fulfilled its role as a rite of passage and Roberts was done with the game. He had suffered a number of concussions and felt he didn’t really love it any more. It was his father who talked him back into playing.

Roberts returned to the game angry and edgy, ready to punish anyone who disrespected him. He knew bullies understood force and fought a constant battle within, wanting to fight anyone that disrespected him. Fighting, he says, “blocked out the anger and confusion and I took my self loathing out on anyone that crossed me”.

Fighting proved he wasn’t weak and provided him the safe refuge of the tough league stereotype. Stereotypes mean less thinking and for the league community, surrounded by a deep emotional moat, there was no way he could be tough and gay.

His father always advised him to “go for the biggest guy” and, crippled by a life in denial, he could sublimate his rage and claw back self-worth by excelling at everything physical, including fighting.

It was all a smokescreen for a new phase of his life, gloriously inaugurated at Sydney gay pub The Exchange. The first time Roberts “went down the rabbit hole”, his life changed forever. There was no macho posturing or aggressive hospitality. Everyone looked different and Roberts was home.

“There were no fights and it was cool, so heteros went there,” he says. “I had a rush of freedom and belonging and saw my first role models, living openly as gay men and women.”

It was the beginning of an astonishingly compartmentalised life. At The Exchange, he could express himself with tailored suits and naval uniforms which would then be packed deeply into the boot of his car “way behind my footy gear”.

Whispers of his nocturnal habits reached his Mascot team-mates. Roberts would convince them that he was going to “50-50 clubs”, further throwing them off the trail by parading with beautiful “girlfriends” at club functions.

In 1984, an unlikely hero emerged for 19-year-old Roberts in the form of New South Wales premier Neville Wran, who passed a law decriminalising homosexuality. “It was such good news that I was no longer committing a crime,” Roberts remembers. “By simply changing a law, I felt safer and stronger.”

It was the same year that Bronski Beat’s tortured coming out anthem Smalltown Boy stormed world dancefloors, crystallising the horror experience in which a young suburban man is bashed for attending a gay club and disowned by his father. Roberts remembers his father watching the film clip and bellowing “That’s disgusting” at the television. The idle comment had an impact on Roberts, “edging me back into the closet”.

The south Sydney area was famed for breeding the roughest players. They drew from working class locales, were often poor and distrustful of outsiders. The precious green spaces offered a level playing field to escape the social injustice. The Rabbitohs sit at the peak of the south Sydney community and in 1986, at the age of 21, Roberts made his debut, stunning his friends and family with his adjustment to first grade football in the Winfield Cup.

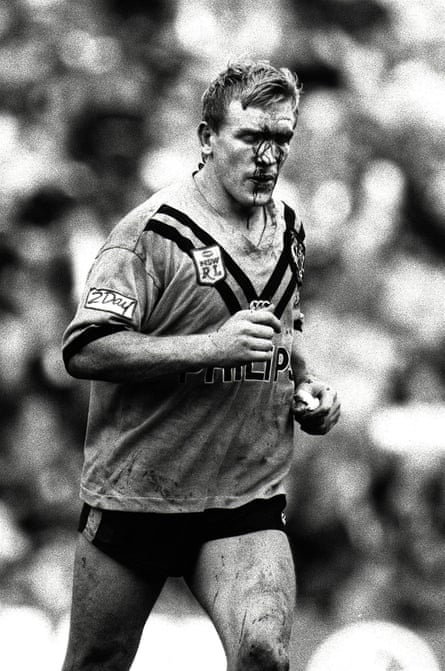

Roberts was quoted in an interview in the Mirror newspaper: “If someone smashes me in the mouth I’ll smack them back. As soon as they see you flinch a bit they’ve got you. You can’t afford to take a backward step.” The South Sydney faithful lapped it up, recognising fighting DNA in their new hero.

Roberts accepted a move to play for Wigan in the north of England in the off-season, where he linked up with New Zealand coach Graham Lowe for the first time. Lowe remembers Roberts’s Wigan stint fondly: “Overriding everything Ian was involved in was his courage, nothing was easy for him.”

Roberts lived with Lowe and his wife Karen during his time in the UK. Neither had any idea he was gay. “He was a good looking man,” Lowe says, “beautiful women came for him but he looked like he was there for footy and nothing else. He was our model for discipline!”

Wigan played the touring Australia side, and Lowe recalls speaking to Roberts before the game, convincing him that he should be in the Kangaroos team and what an opportunity he had to prove that to the selectors. “Like a colossus he took the Aussie pack on himself and it shocked both them and us.”

Due to his British passport, Roberts had played for Wigan as a local player and impressed the Great Britain management. He was offered the opportunity to switch to Great Britain but Roberts turned it down citing “unfinished business”. Lowe was amazed, saying at the time: “Australia is lucky he is so fiercely loyal. I’m stunned he is not in the Australian side.”

Roberts returned to Sydney with renewed confidence. Fellow Mascot junior Fenech witnessed his meteoric rise first hand: “We knew that Ian was something different, a new breed,” says Fenech, who grew up in an era of slow, short “Clydesdale” props. “He was the revolution – tall and super fit, an amazing thoroughbred athlete, could jump through the air and catch the ball like Superman, he could attack, he could defend and give you 40 tackles a game.”

Off field Roberts continued the game of Russian roulette featuring secret boyfriends and increasingly urgent inquiries from team-mates. Eventually old school Souths coach George Piggins confronted Roberts about his sexuality, pleading with him to stop going to the gay clubs. “You’re getting yourself a bad name,” Piggins told him. Roberts replied that he went there for the music, “my default setting excuse”.

There is no cure for curiosity and Roberts’s continued subterranean lifestyle lent weight to suspicion. Early in the 1989 season a gossip item written under a nom de plume appeared in the Sun Herald stating Roberts had been spotted in a gay club. In the following game Roberts was baited by Bulldogs players and openly vilified by fans, the thought of a gay player fuelling the passions of the wildest elements.

The same year, Roberts shocked Souths fans by signing mid-season with Manly, becoming the game’s highest paid player and reuniting with Lowe, who convinced him he could guide him to play internationally. This devastated Piggins, who had earlier declared Roberts as “Souths’ greatest junior” and “the best player in the game”.

Roberts received a torrent of hate mail including threats to his parents, who stopped attending games. He had previously knocked back big-money offers from Wigan and Penrith, and his ratty 10-year-old Datsun was the fruit of his loyalty to Souths.

Roberts remembers two standout moments in his time at Manly, the first being a big hit on St George’s Michael Potter followed by air punching, teeth baring and an emotional scream. Roberts says with a laugh: “It had nothing to do with poor Mick Potter and everything to do with my anger at the world.”

The other was a fight in which he administered a beating to Balmain Tigers’ Garry Jack that resulted in stitches and plastic surgery. The matter was settled in court with Roberts ordered to pay $50,000. He can’t comment on the matter other than offering: “I was in the wrong and was very happy to pay Garry the money to make it right.”

All the while, Roberts maintained his chameleon lifestyle, but keeping everyone guessing with measured ambiguity took its toll. He suffered depression for the first time, coming close to killing himself having become emotionally stunted through constant lying and denial.

In 1992, at the age of 27, Roberts decided to tell his parents about his sexual identity and stop “protecting them” from the truth. It was a classic kitchen table confession which left them in disbelief. Roberts’s father Ray took it well, unlike his mother, who was angry. His father came through for him. “You’re still our boy and as long as you’re a good man that’s all that counts,” Roberts remembers him saying. Roberts was bone tired from pretending, but they both advised him to keep it a family secret until after his career.

Two years later Roberts tormented rugby league media and fans further by agreeing to a nude shoot in Blue, a new gay magazine, but did not definitively say he was gay. The opposing crowds went wild and the homophobic abuse grew to new heights. Importantly he had dipped his toe in the water and it was only a matter of time before the informal would be formalised.

Most of the Manly players knew his sexual identity and were accepting, even welcoming his boyfriend Shane to be the Sea Eagle mascot at games. Roberts continued to play the media game using female friends as “decoy girlfriends”, and his sexuality was now widely discussed in the league community.

Although Roberts’s sexual identity was the worst kept secret in rugby league, he was still under intense pressure to put the final nail in the coffin and come out publicly. For the gay community, sexuality was a matter of life and death. Gay bashings and killings were rife across Sydney, creating a siege mentality. Many in the community viewed Roberts’s coming out as a way to save lives, particularly with high rates of gay teen suicide blamed on a lack of positive role models. There were threats to be “outed”, as a footballer offered a unique bridge to the mainstream. Roberts was a “high value prisoner” for the community – for them silence was complicity and his privacy was a small price to pay.

An ARL staffer advised Roberts that coming out publicly would mean less sponsorship, using Martina Navratilova as an example. Roberts appreciated the honesty but could not buy in to the belief that the fans and sponsors would not tolerate a gay man.

“If someone asks me about the financial side of coming out I let them know that the ‘pink dollar’ is very elusive,” he says. “Don’t come out for financial reasons.”

After an agonising appraisal of his life, in 1995 Roberts came out officially in Australia with a story in New Weekly titled “A man and his match” detailing his relationship with his then boyfriend Shane.

For Roberts it was a sobering and cathartic moment and the public response oscillated from joy to horror. Peter FitzSimons in the Sydney Morning Herald was clear on the impact of the announcement: “Roberts is not the first gay footballer, but the first with the courage to live it openly. Surely the wretched schoolyard taunt of ‘yer a poofta’ has lost an awful lot of sting.”

Roberts received thousands of letters of support, including some from grateful parents and teachers on how he had changed and saved lives by providing a role model. He was saving kids from killing themselves and people were grateful that he had provided an option for a life of remorse and sorrow for not “fitting in”.

Hate mail also flooded in, and people stopped him in the street to quote Scripture and confirm he was on a “highway to hell”. Some thought he should be put in a cage and poked with sharp bamboo.

Roberts decided to escape the Sydney bubble and moved to Townsville, a stint with the North Queensland Cowboys providing the critical distance he needed, and he enjoyed his football more than any time of his career. Coach Tim Sheens liked what he saw and made Roberts the captain. After two seasons, Roberts retired at 34.

He looks back at his role as an important one. “In the 90s gay men were murdered and bashed by vigilantes. There used to be moments of silence at the Sleaze Ball for these murders but, much like Aboriginal deaths in custody, mainstream media didn’t want to know.”

Over the past 20 years he has received a lot of mail from parents and teachers in small country towns, confirming that their child or student had come out, inspired by his bravery. “That telling the truth could change something. I didn’t appreciate it at the time but it’s had a huge impact downstream,” Roberts says.

Roberts has been the industry confidant for a number of league players and players in other codes who have contacted him about coming out. Roberts says: “I can’t offer them much, particularly those locked into marriages. You have to stick your nose above the wall of fear and say it. Most don’t understand what I mean when I tell them the truth will set them free. You feel it physically as well. Once you’ve come out it never ends. You have to keep coming out with every new person you meet who has a jolt when you mention your boyfriend.”

Yet life is good for Roberts. His long-term partner Dan is a kindergarten teacher, and he has just picked up three weeks’ acting work. In a 12-year acting career since hanging up his boots he has had roles in 40 film and television projects including Underbelly, Little Fish, Dancing with the Stars and Sea Patrol. His highlight? “Getting to bash Superman.”

What has he learnt on the journey? Bravery and humour are the two themes: “Be loyal to yourself and your values and walk as close as possible to what you believe in. Running from fear is avoiding growth. And humour heals. You have to have a laugh.”

His old coach and mentor Lowe understands Ian’s contribution more than most: “He was a trailblazer in many ways. There are few people like him – everybody he meets is better off for the experience. He never takes himself too seriously and can look at the gravest situations with a smile. I have two twin boys and to me Ian is like another son.”

Roberts is happy to hear that finally Hirst has followed in his footsteps and “taken the leap” by going public with his sexuality – just the second active rugby league player to do so. “It must have been difficult for him to admit he’s gay, from a tough town with zero tolerance,” he says.

“I truly believe in equality and Keegan’s story will only be really powerful when it is no longer considered brave or admirable, just truthful. Like me he has faced the moment when you realise that everything you grew up believing to be real is just the false reality of conformity and keeping you in your place.”

Moments and events accumulate to create change and as the first gay contact sport player to come out during a career, Ian Roberts sits with sports diversity pioneers Jackie Robinson and Martina Navratilova. Bearers of light who left an indelible mark by braving the jeers to be true to themselves.

Easing back into his chair and pondering his life choices, the once tough-as-nails working class kid feels like a grizzled combat veteran whose war is not over. Roberts says wistfully: “Some say I was brave, some say I was foolish but at 50 I’m at peace with who I am, but would love to know where my special niche to help people is. My coming out was a false dawn, change has enemies and there is a lot of work to be done.”

After a recent Labor meeting at a pub in Redfern he was approached by an old Aboriginal man, who said he liked him because he stuck by his mob. Roberts relays the story with a big smile. “It’s the greatest compliment I’ve ever received.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion